Paranoia is an intriguing and often stigmatised psychological condition characterised by chronic and unwarranted suspicions of others. While it is commonly associated with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, paranoia can also manifest independently in individuals without any diagnosed psychiatric condition. In recent years, researchers have delved deeper into the neurobiology of paranoia, unravelling the complex workings of the brain to shed light on this perplexing phenomenon.

1. Understanding the Concept of Paranoia

Paranoia is often misunderstood as a mere irrational fear. However, it is important to recognise that genuine paranoia extends beyond occasional mistrust or heightened vigilance. In fact, paranoia involves chronic and pervasive feelings of suspicion, resulting in profound distress and interference with day-to-day functioning. By studying the neurobiology of paranoia, scientists aim to gain a deeper understanding of the brain processes intricately involved in fuelling these persistent beliefs.

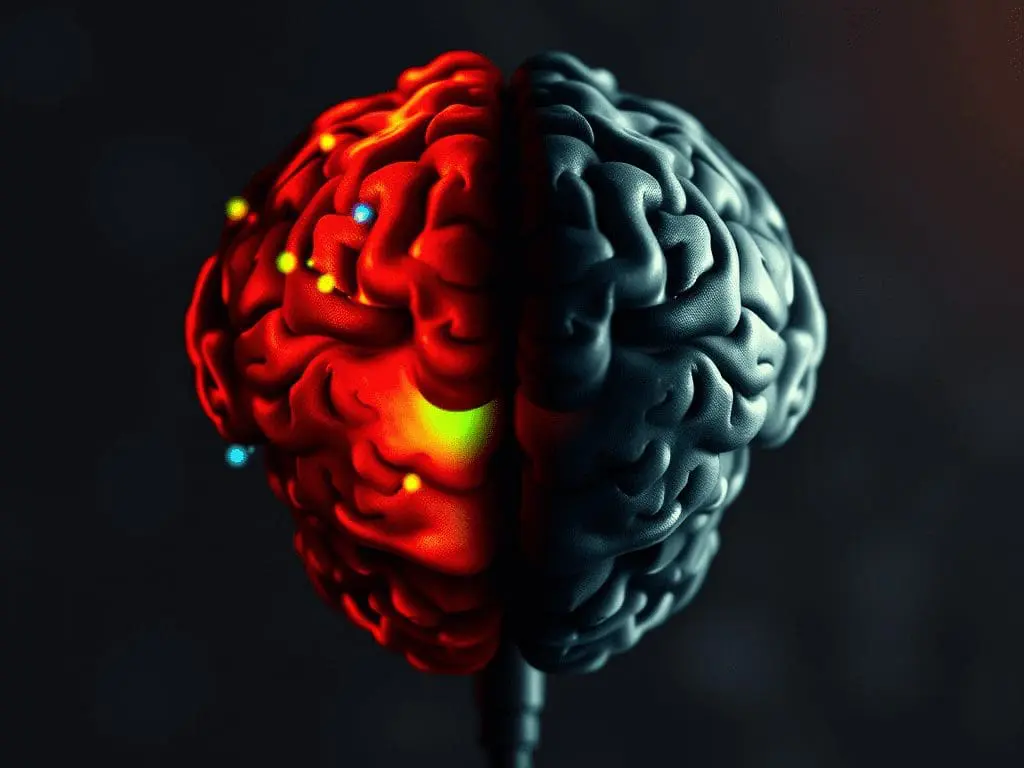

2. The Role of the Amygdala

One key brain structure implicated in paranoia is the amygdala, known for its crucial role in processing emotions, particularly fear. Numerous studies have shown that the amygdala appears overly sensitive in individuals with paranoia. This hypersensitivity leads to exaggerated responses to potential threats, driving the heightened fear and anxiety often experienced by those with paranoid thoughts. In this way, an overactive amygdala might contribute to the development and maintenance of paranoid beliefs.

3. Cognitive Biases and Dysfunctions

Paranoia is not solely rooted in abnormal emotional responses. Researchers have found evidence suggesting that cognitive biases and dysfunctions also play a substantial role in reinforcing paranoid thoughts. For example, individuals with paranoia tend to display heightened threat detection abilities, often interpreting neutral or ambiguous cues as evidence of impending harm. Additionally, they exhibit a tendency to assign malevolent intentions to benign actions, distorting their perception of others’ motivations. These cognitive biases perpetuate and solidify paranoid beliefs, further fuelling the severity of the condition.

4. Brain Connectivity and Paranoia

Emerging research in neurobiology has also highlighted alterations in brain connectivity associated with paranoia. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies have shown disrupted connections between key brain regions involved in information processing and emotional regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala. These connectivity disruptions may underlie the cognitive biases and emotional dysregulation observed in individuals with paranoia.

Conclusion

Paranoia remains a captivating subject within the realms of neurobiology, sparking ongoing investigations into its underlying mechanisms. By exploring the neurobiological basis of paranoia, researchers aim to develop more effective treatments and interventions to alleviate the distress experienced by individuals struggling with this condition. Understanding the interplay between brain structures, cognitive biases, and altered connectivity can pave the way for developing therapies that target these specific areas. Ultimately, unravelling the neurobiology of paranoia could have implications not only for those directly affected by it but also for broader discussions on trust, social cognition, and mental health in general.